John Akomfrah

7 – 13 April 2014

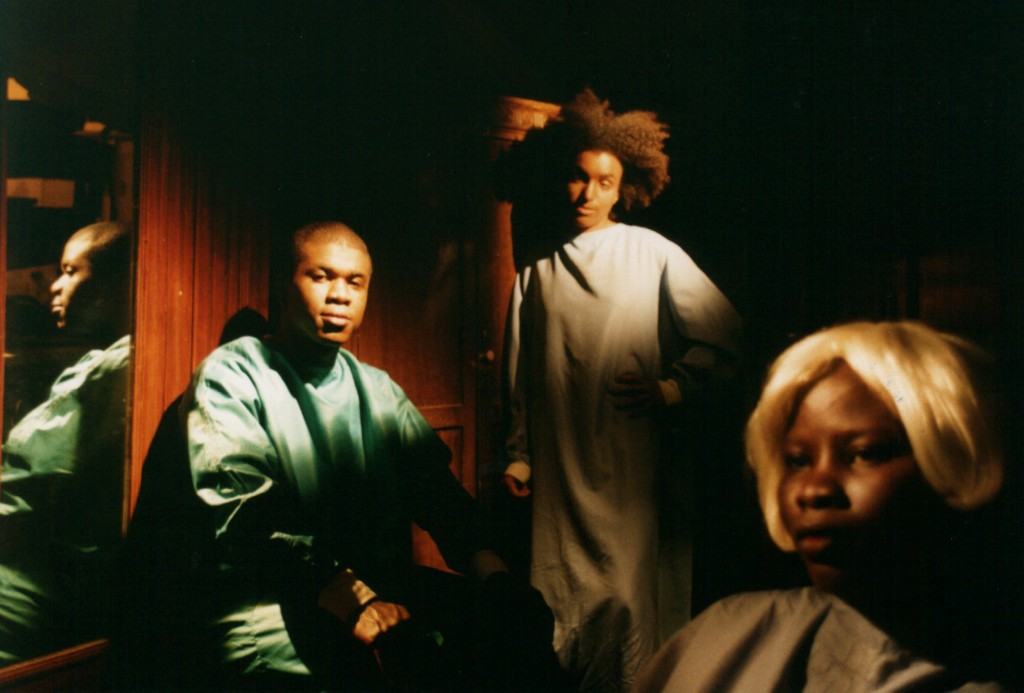

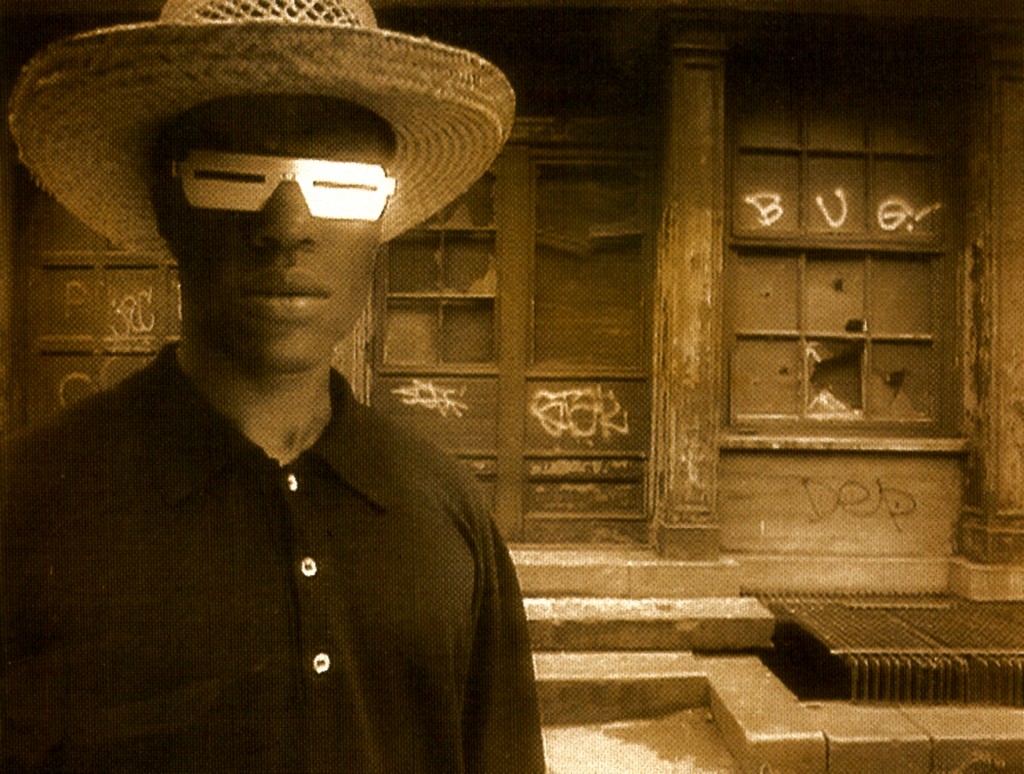

The Nine Muses (2010)

Homer’s The Odyssey, the primary narrative reference point for The Nine Muses, begins twenty-five years after the end of the Trojan War. Odysseus still has not returned home, so his son, Telemachus, sets off on a journey in search of his lost father.

Structured as an allegorical fable set between 1949 and 1970, The Nine Muses is comprised of nine overlapping musical chapters that mix archival material with original scenes. Together, they form a stylized retelling of the history of mass migration to post-war Britain through the suggestive lens of the Homeric epic – ‘stories usually seen through the lens of post-colonialism could as easily be viewed through the lens of mythic history’.

Alongside Homer’s epic, The Nine Muses, calls upon the writings of a wide range of authors including Dante Alighieri, Samuel Beckett, Emily Dickinson, James Joyce, John Milton, Friedrich Nietzsche, William Shakespeare, Sophocles, Dylan Thomas, Matsuo Basho, TS Eliot, Li Po, and Rabindranath Tagore.

___________________________________________

“I’ve been obsessed for a long time with something I read in Derek Walcott’s Omeros, where he talks about diasporic lives being characterised by an absence of ruins. There are no monuments that even as ruins attest to your existence, of your passing through a space. This then means that the intangibles, be they sound or words, become necessary building blocks. Lives that are not legitimised in the official monument can then be given a certain kind of legitimacy.

That’s very important in The Nine Muses. The very construction of it is about trying to say something of the migrant narrative. It’s not a completely foreign thing brought over and it’s not just from Britain, it’s an amalgam of these two things. And I wanted the soundtrack, broadly put, to mirror that. By that I mean not simply the “music” but also the words; the cadences and rhythm of words and exactly what sorts of words are seen to coexist with the music.”

-John Akomfrah

(From: http://www.soundandmusic.org/features/sound-film/interview-john-akomfrah)

“The Hyphen, Black-Britishness…”

For Akomfrah, using multiple voices rather than one narrator is part of his commitment to allegory, which is also informed by music and intertwined with a blues aesthetic, “in the sense that none of it is on the note, none of it is on the beat, but you kind of garner from it what’s going on. It’s that thing of just not hitting anything straight.”

Using this allegorical method, Akomfrah works towards destabilising received histories about how “the hyphen, Black-Britishness, was created”. And he identifies this lack of historical imagination as a symptom of received artistic and representational structures themselves, such as conventional documentaries or traditional forms of composition: “Documentary is exactly like the symphony when Schoenberg and that crowd encountered it… It was completely ossified, formulaic. [It had] this almost fossil-like symphony structure to it: here’s an intro, this is the story of how black people came to Britain, and then it’s rounded off and the story starts. The whole kind of boring, meaningless, slavish attempt at propping up some fiction and myth of Britishness and how Black-Britain became, I’m not interested in that, that is not what we’re doing here.”

(From: http://www.thewire.co.uk/archive/artists/john-akomfrah/john-akomfrah_the-nine-muses)

“What I am more interested in is the notion of the hyphen. How hyphens come about, which seems to me to be much more suggestive, and seems to escape some of the raciological trappings of hybridity. It is those raciological trappings that I can sense you have a certain discomfort with. I do too, but I don’t share it because I don’t believe quite as much in the explanatory power of hybridity as I did maybe twenty years ago…

I’ve turned circles around this notion of the hybrid, ever since the 1980s. If we remove it from the field of identity politics for the moment and apply it to the question of aesthetics, the question of hybridity has been very important for us. It implies that we haven’t necessarily had to swear allegiance, for instance, to the existing set of genres and modes of address and cultural practices which were available to us. People would endlessly ask me, do you make art or cinema? Are you doing documentaries or feature films? Where is the place of the historical in these works, which clearly flirt with notions of historicity, but which also seamlessly attempt to weave them with fictional scenarios?

I would routinely say that we have a kind of agnostic relationship to a number of these genres. I can’t swear full allegiance, let’s say, to the documentary because most of the documentaries in their origins—because the modes of address that they set up—have not been flattering to people of African descent. I have no reason, unlike some of my European counterparts, to feel that the history of the documentary is one that I feel kinship with. We all know and we’ve all talked over the years about the racism of some of the early founders, D.W. Griffiths and so on. My point is this: since the history of the forms that I work with are already “contaminated”, an appeal to the hybrid becomes both the defining gesture as well as the conditions of existence of one’s engagement with those forms. One of the ways in which one tries to see through the impasse is by working with what used to be called a “recombinant aesthetic”, whereby every element from these available narratives and genres was drawn upon, without swearing wholesale allegiance to them.

Now it seems to me that in that sort of context, the notion of hybridity does have a use because it connotes a certain descriptive accuracy when it is applied. My problem with it is when it begins to migrate from that space and into the field of identity, and particularly into the field of identity formation. I disagree with the deploying of hybridity essentially for what Paul Gilroy calls “racialogical purposes”. I don’t want to completely let go of the notion of the hybrid, I just want to limit the areas of its use and the values that one ascribes to it.

The reason why I say that I am much more interested in the hyphen is also because it poses cultural and intellectual challenges for me that I am trying to get my head around. Take, for instance, the notion of the “afropolitan”. The notion of the afropolitan has exactly the same sort of problems that hybridity had before. As a descriptive category, the afropolitain is trying to understand patterns of traffic, both cultural and identitarian, across the world. It is trying to find a way of discussing and understanding how someone such as David Adjaye might come about: someone born in Ghana, raised in Dar es Salaam, and who works in Europe, et cetera. We have to find ways of describing these identities without then setting up a hierarchy in which they appear to be more civilized, more “advanced” than the so-called “common” African who hasn’t had the experience of living in Dar es Salaam and/or other places. I can understand the ethical dimension to the problems we have but I don’t want to put the cart before the horse. Both terms are trying to understand patterns across the post-World War planet and we need to turn our attentions to how to do that without them becoming the problem that you are describing.”

-John Akomfrah

T. S. Eliot – Journey of The Magi

A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.’

And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory,

Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

And running away, and wanting their liquor and women,

And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night,

Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying

That this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley,

Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;

With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness,

And three trees on the low sky,

And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.

Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel,

Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver,

And feet kicking the empty wine-skins.

But there was no information, and so we continued

And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

John Milton – Paradise Lost: Book I (extract)

Of Man’s first disobedience, and the fruit

Of that forbidden tree whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, till one greater Man

Restore us and regain the blissful seat,

Sing, Heav’nly Muse, that on the secret top

Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire

That shepherd who first taught the chosen seed

In the beginning how the heav’ns and earth

Rose out of Chaos; or if Sion hill

Delight thee more, and Siloa’s brook that flow’d

Fast by the oracle of God, I thence

Invoke thy aid to my advent’rous song,

That with no middle flight intends to soar

Above th’ Aonian mount, while it pursues

Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme.

And chiefly thou, O Spirit, that dost prefer

Before all temples th’ upright heart and pure,

Instruct me, for thou know’st; thou from the first

Wast present, and, with mighty wings outspread,

Dove-like sat’st brooding on the vast Abyss

And mad’st it pregnant: what in me is dark

Illumine, what is low raise and support,

That to the highth of this great argument

I may assert Eternal Providence

And justify the ways of God to men.

Rabindranath Tagore – My Friend

Art thou abroad on this stormy night

on thy journey of love, my friend?

The sky groans like one in despair.

I have no sleep tonight.

Ever and again I open my door and look out on

the darkness, my friend!

I can see nothing before me.

I wonder where lies thy path!

By what dim shore of the ink-black river,

by what far edge of the frowning forest,

through what mazy depth of gloom art thou threading

thy course to come to me, my friend?